Rare Medieval Music Manuscript Returns to Buckland Abbey

The west front of Buckland Abbey, Devon

For the first time in nearly five centuries, Buckland Abbey in Devon will resonate again with the sacred sounds of monastic music thanks to research into a rare 15th century manuscript.

A Cistercian abbey now in the care of the National Trust, the abbey was once the home of resident monks and choirboys singing for hours every day, but fell silent during King Henry VIII's purge of religious houses in England.

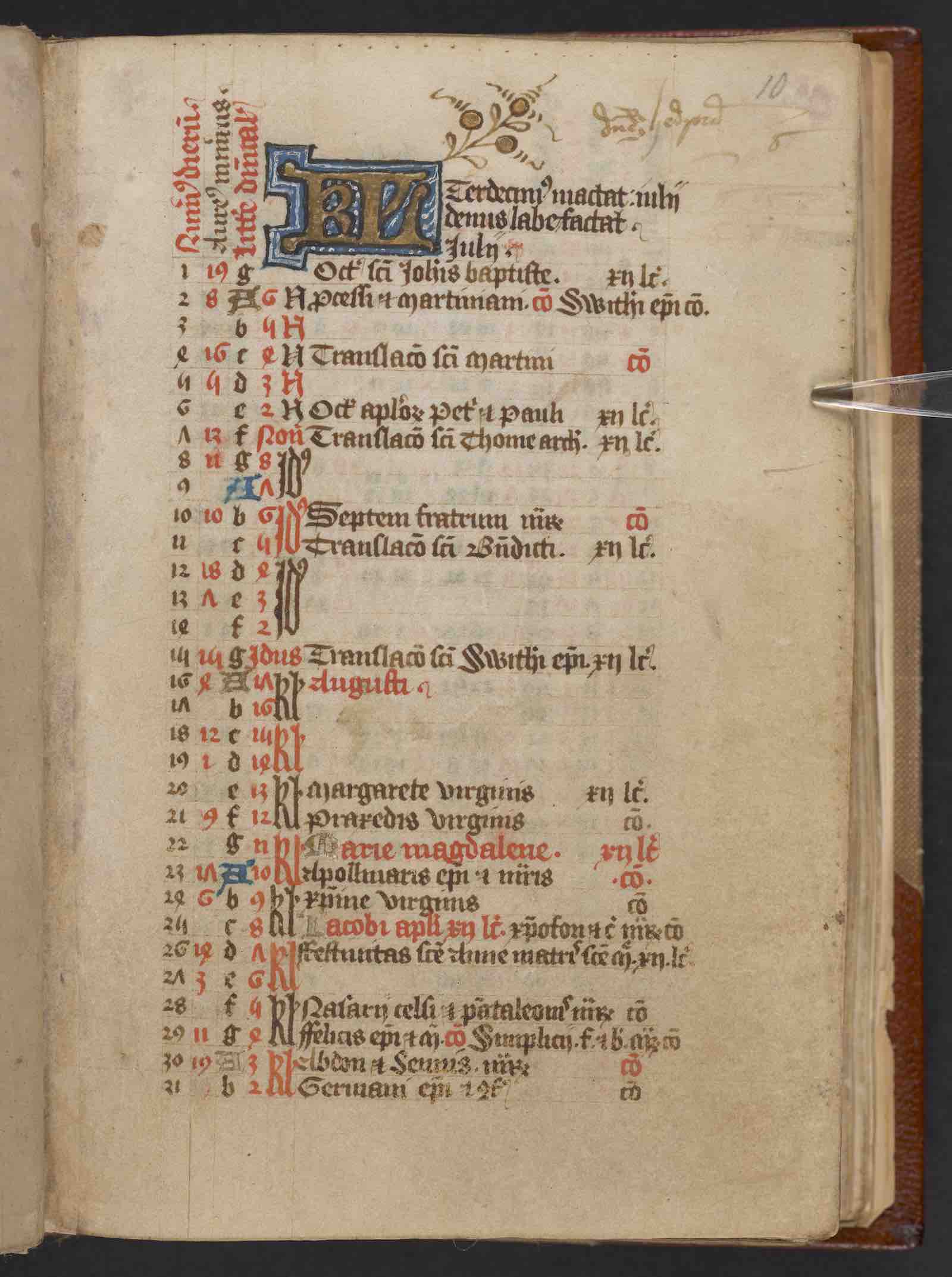

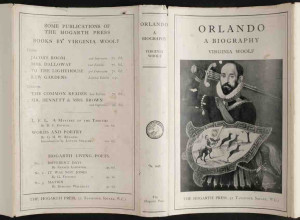

The richly decorated Buckland Book (c. 1450) known as a ‘customary’ contains the instructions the monks needed to carry out their daily religious rituals and services. Unusually, it also contains a rare collection of medieval music copied and added to the book in the early Tudor period. Once owned and used by the abbey, it is now part of the British Library’s collection and will return on loan to Buckland Abbey for the first time since its 16th century dissolution with its music heard once more thanks to the University of Exeter Chapel Choir.

University of Exeter historian, Professor James Clark, first noticed the music while researching Buckland Abbey’s monastic past on behalf of the National Trust. Hardly any of the music performed in England’s medieval monasteries now survives because their books were lost or destroyed during the Tudor Reformation.

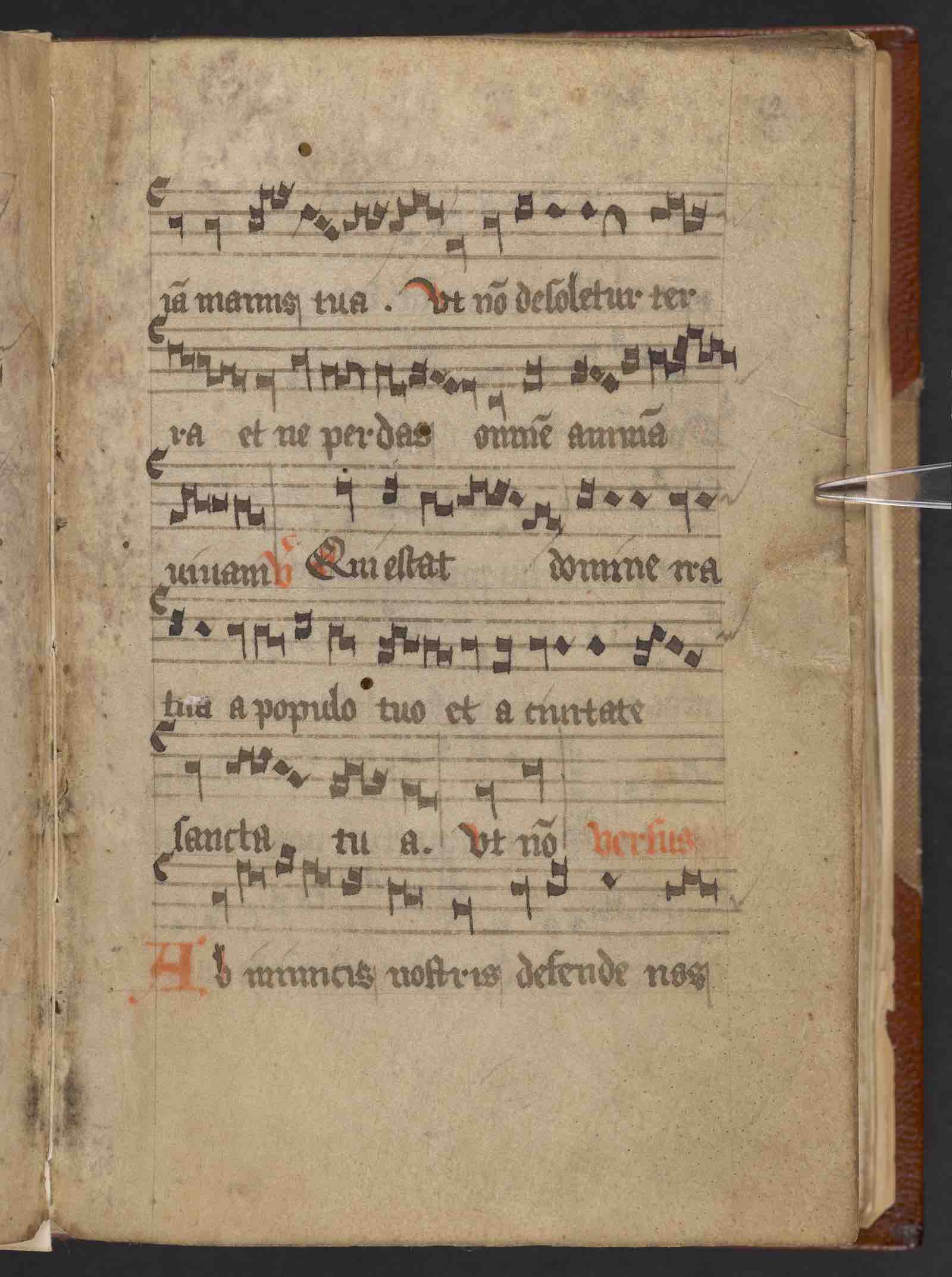

The music is in ‘plainchant’, with single lines of music for monks or priests to sing all together. What makes the music more unusual is that rather than following the rigid liturgical structure of the time, with particular pieces sung at different times of the day, the monks curated a unique sequence of chants drawn from various sources.

“Whoever compiled this collection seems to have been unusually creative, pulling together words and music from many different sources," said National Trust Research Officer and music historian Daisy Gibbs. “The pieces found in the book ask for God’s mercy, forgiveness and protection from harm. They share a real feeling of anxiety and fear. It looks as though they were once sung as a complete sequence, perhaps to help the monks through a crisis of some kind."

The music may have been intended as a response to the sweating sickness which broke out repeatedly in Tudor England. Henry VIII’s Chief Minister Thomas Cromwell lost his wife and two daughters to the disease.

The Buckland music is also unusual because we know the name of the abbey’s choir master and organist from this time. Robert Derkeham began living and working at the monastery in 1522 and stayed there for more than 15 years, until it closed and he was pensioned off. It’s exceptionally rare to be able to connect a book of medieval music like this with the specific musician who performed it.

Working in partnership, the National Trust and University researchers have now transcribed the music for its first performance in nearly five centuries. The University of Exeter Chapel Choir has recorded the music, bringing the voices of the long-lost monks back to life (click the link below to listen).

The recording will form part of the soundtrack to a new exhibition featuring the manuscript, Opening the Buckland Book: Music and community in a Tudor monastery running July 5 through October 31. The University of Exeter Chapel Choir will also perform the music live in Buckland Abbey’s medieval Great Barn on August 16 and 17.

“Having searched the archives for traces of England’s lost abbeys, it is very exciting to recover something of their sound," said Professor Clark. "Before the Tudor Reformation, in every part of England and Wales there were places like this dedicated to creative music-making and performance. Through this research we can now learn much more about this tradition and what it meant not only for the musicians but also for the surrounding communities that shared in their art.”

Michael Graham, the University’s Director of Chapel Music, added: “Although the music is written down using the same notation that’s still used in the modern Catholic Church, it doesn’t give any instructions about rhythm or dynamics, so we had to make decisions about how the pieces should sound. This is one of the most interesting, and also most challenging, parts of performing music that’s over 500 years old!

It is not clear what happened to the Buckland Book between the closure of the abbey and when it was acquired by the Harley family in the 1720s, before being sold to the British Museum in 1753. One possibility is that one of the monks took the book with him, and it remained quietly on a shelf after a hoped-for reversal of the Dissolution which did not come.